MATHLETES: Baseball and Blood Lines

[Kenneth Zemsky note: Yes, I'm biased but this is the best baseball article I've read in a long time.]

Have you ever noticed the number of major league baseball players with fathers who have also played in the MLB? The laws of statistics tell us that at any given time, only one child of a former major league baseball player should himself make it to the big leagues. However, the actual current crop of MLB offspring is almost 40 times greater than that. Why? Is this statistical anomaly attributable to a fluke, genetics, training, existence of an old boys’ network, or some other factor?

Listening to games last season, the number of times an announcer would introduce a player as the “son of former big leaguer John Doe” itself seemed to defy the odds and merited a deeper look. Moreover, simple math concepts exist to provide the analysis. One need not be an expert in differential calculus or a sabermetrician. From the fan’s perspective, sports and certainly baseball are statistically driven, and basic understanding of mathematics can enhance one’s appreciation of the sport.

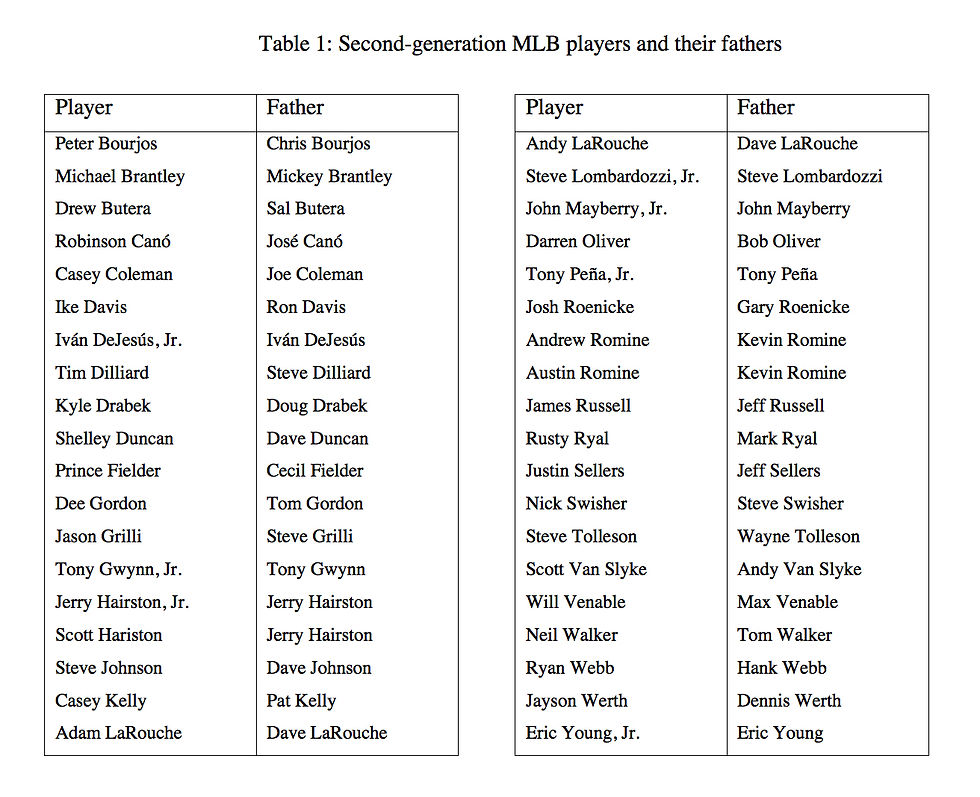

Table 1 below lists the ballplayers on big league rosters in 2013 along with their major league fathers. It is worth noting that at least two of the players, Robinson Cano and Prince Fielder, have numbers that cannot be denied and justify their presence in the major leagues. The group as a whole represents a bell-shaped curve of talent.

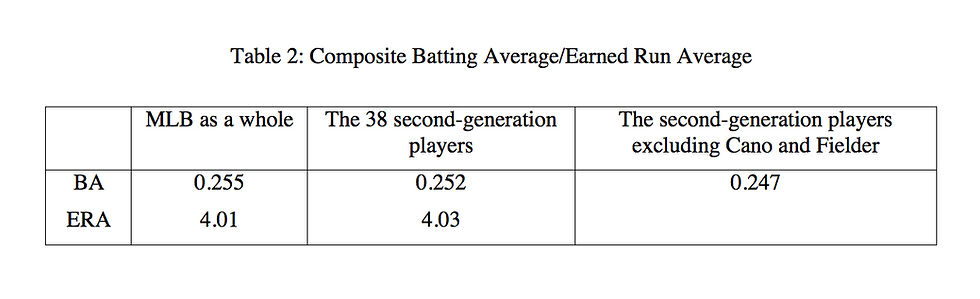

The next table shows the composite batting average/earned run average of

the big league offspring, both with Cano and Fielder’s stats included and excluded, as compared with the league totals. According to these stats, it is clear that the pool of talent of baseball offspring is not demonstrably superior to other players.

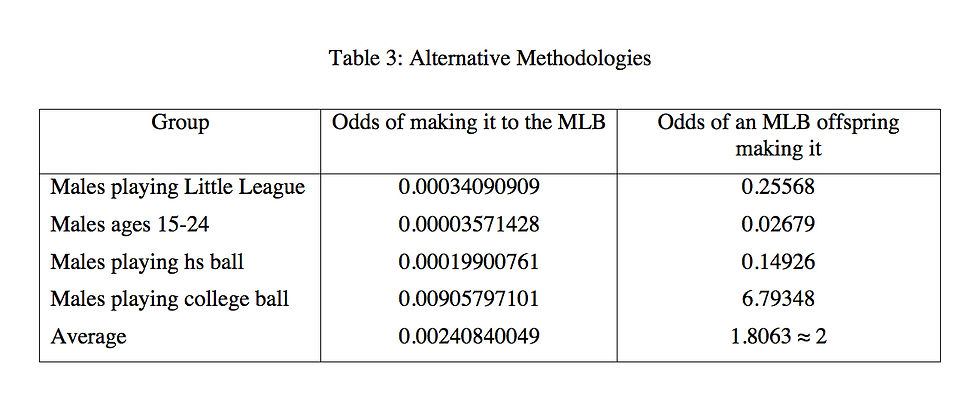

Let’s now look at the odds of making it to the big leagues. The MLB consists of thirty teams each with an active roster of 25 players, so there are 750 available positions. Using Little League as representative of every red-blooded American boy’s dream to play professional baseball, there were approximately 2,200,000 children who played in the Little Leagues in 2013. Seven hundred fifty available positions divided by the pool of 2.2 million means the odds of a Little Leaguer making into the major leagues are about 0.0003409 or three hundredths of a percent. Now, applying this percentage to a past pool of 750 baseball players, then the number of their children who should make it to the big leagues is 0.255682. Since we cannot carve people into fractions, we round up to one. Rounding up also provides simplification in that it offsets other variables, such as length of time in entering the big league pool. Note that several assumptions have to be made:

All boys who want to play professional baseball play in Little League.

Of the 750 big leaguers, there are 750 of their sons who want to follow in Dad’s footsteps and play Little League.

The pool of MLB fathers producing MLB offspring covers a similar time span as the age span of Little League play.

To view the percentage differently, table 3 provides a similar analysis not just of Little Leaguers, but also of all American males ages 15-24, all students playing high school ball, and all students playing college ball. Applying the average of all these results increases the odds of MLB offspring making it, from one to two players. Even this increase is dwarfed by the actual number of 38 players as depicted in table 1.

If math concepts do not lie (one plus one is always two), and the composite average of big league offspring is not greater than the numbers posted by players who did not have famous fathers, then we must discount the likelihood of a statistical fluke.

What about heredity as a factor? When asked if genetics plays a role in athletic ability, Dr. Geoffrey D. Findlay, professor of biology at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts said, “Anytime a geneticist studies something like this, it's called a complexity type. There are lots of things that go into how and what makes someone good." Genes, of course, are the units of heredity, made up of DNA, that act as codes that determine a person's characteristics. Height, weight, eyesight, hand-eye coordination, and strength are among these. Dr. Findlay gave a simple example of two left-handed parents and their chances of having a left-handed child. Left-handedness is a recessive trait and only two left-handed parents might have a left-handed child. In baseball, batters are more frequently exposed to right-handed pitching, giving left-handed hurlers an automatic advantage. The advantage lies in the pitchers’ genetic make-up for handedness. When other genetic factors are considered together, the issue becomes more complicated. In trying to estimate how much of athletic ability is genetic, Dr. Findlay pointed out that research has found that it widely varies from 20-80%. It is difficult to get an accurate percentage since there are so many factors to consider in measuring athletic performance.

Dr. Findlay raised an additional consideration: “How much is it genetics? How much is it environmental?" This adds another complicating factor in trying to quantify athletic performance. One’s culture, training, and practice could contribute as much as hereditary characteristics. According to Dr. Findlay, "People who grew up with a baseball player for a dad might be pushed to go into baseball more. The dad might have access to better opportunities, such as coaching."

Long time voice of the New York Mets, Howie Rose, agreed that having a big league father helps in terms of knowing how the system operates. “They know their way around the big league club house; they understand the culture. They understand the significance of big league life in every aspect, from travel to the off-the-field activities or demeanor with fans. They just have an inherent advantage of having had a father who knows the ropes."

Rose added an important caveat. “Only the supremely gifted succeed and only those supremely gifted players who have the will to succeed can succeed. The skills required to play in the major leagues are so specific and so above and beyond the norm. They're God-given and those things tend to carry on generation to generation on varying level. Still, the offspring of professional athletes are, generally speaking, born with that gift, the gift to excel athletically. Whether they take it all the way to the highest level is another story." Thus, it is not always the case that an amazing ballplayer will have a son who is equally successful. As Rose puts it, "For every Barry Bonds, there are a thousand Lee May Jr.'s." Bonds, of course, is the son of Bobby Bonds, whereas Lee May Jr. was a first-round pick who did not match his father’s prowess on the field. “It's an inexact science to be sure but it's quite genetically linked," Rose stated.

Accordingly, culture, training, and determination are contributing factors, though bloodlines confer an absolute advantage. In Howie Rose’s pithy summary, “When it comes to making it to the big leagues, I would throw math completely out the window.” When executives, general managers, and scouting directors are torn between two prospective draftees, “if one of those players has bloodlines, meaning someone in their family, they will invariably give that player the benefit of the doubt. That’s the tiebreaker for sure.”

In any event, math and science provide another dimension, enriching enjoyment of spectator sports. The topics of potential enrichment are boundless. For example, what is the statistical likelihood of someone breaking DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and which player is likely to do it? Is there a mathematical/financial benefit to playing for the Yankees (New York State/City have the highest tax rates in the country) versus the Marlins (no income tax in Florida)? Do games in April really count as much as games in September during the stretch run? The possibilities, mathematically and appropriately speaking, are infinite.

Marisa C. Zemsky is a sports fan who recently received her Master’s with Honors in Applied Mathematics from Worcester Polytechnic Institute.